Learn the cases of German nouns and pronouns

Cases of German nouns and pronouns

In this lesson , we will introduce the cases of German nouns and pronouns . As we noted previously when we introduced the concept of case for pronouns , there are four cases used in German . Recall that the nominative case in German corresponds to the subjective case in English and applies to nouns and pronouns used in a sentence as the subject of a verb . Nouns (and pronouns) that we used as objects of transitive (action) verbs are in the English objective case . If these are direct objects , then these nouns are in the accusative case in German . If indirect objects , then these nouns are in the dative case in German.

Essentially, the English objective case is divided , in German , into an accusative case used for direct objects and a dative case used for indirect objects .

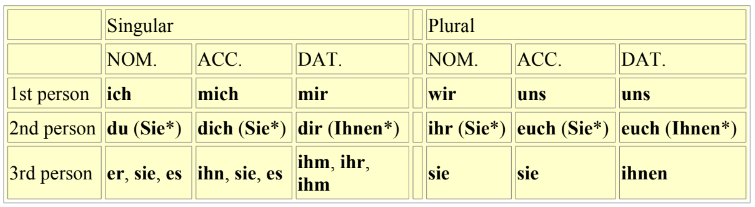

Pronouns

For comparison with English, recall that the singular personal pronouns (nominative case) are “I”, “you”, and “he/she/it” (1st, 2nd, and 3rd persons) . The objective case , personal pronouns in English are “me”, “you”, and “him/her/it”— and are used for both direct and indirect objects of verbs . For example :

| He gives it [the Direct Object] to me [the Indirect Object] |

The German accusative case , personal pronouns (singular) are : mich, dich, ihn/sie/es . The German dative case , personal pronouns (singular) are : mir, dir, ihm/ihr/ihm . Thus , the above English example sentence becomes , in German :

| Er gibt es [the Direct Object] mir [the Indirect Object]. |

Because mir is a dative pronoun , there is no need in German to use a modifier as in English , where “to” is used as a signal of an indirect object . The following table summarizes the German pronouns in three cases for both singular and plural number :

Nouns

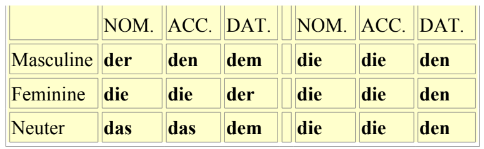

Nouns do not change their form (spelling) relative to case in German ; instead, a preceding article indicates case . You have learned the nominative case definite and indefinite articles (der, die, das and ein, eine. ein) for each of the three noun genders . Now we will learn the accusative (used to signal a direct object) and dative (used to signal an indirect object) articles . First , the definite articles :

![]()

This table might seem a bit overwhelming , but some points to note can make memorizing much easier . First , as you can see from the table , gender does not really exist for plural nouns . No matter what the noun gender in its singular number , its plural always has the same set of definite articles : die, die, den for nominative , accusative , and dative cases . The plural der-words are similar to the feminine singular der-words , differing only in the dative case .

Another point : the dative for both masculine and neuter nouns is the same : dem . Finally , for feminine, neuter, and plural nouns , there is no change between nominative and accusative cases . Thus , only for masculine nouns is there a definite article change in the accusative compared with the nominative .

The following examples demonstrate the use of the definite article in various parts of speech :

| You have the sausage and the cheese. (accusative case) | Du hast die Wurst und den Käse. |

| The business associates understand the work. (nominative and accusative cases) | Die Geschäftsleute verstehen die Arbeit |

| Zurich is the largest city. (nominative case) | Zürich ist die größte Stadt. |

In the last example , you need to know that in both English and German , the noun (or pronoun) that follows the verb ‘to be’ is a predicate noun , for which the correct case is the nominative . That is why , in English , ‘It is I’ is grammatically correct and ‘It is me’ is simply incorrect .

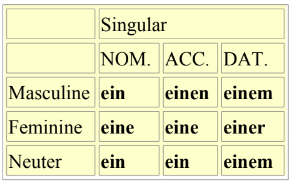

The indefinite articles are as follows :

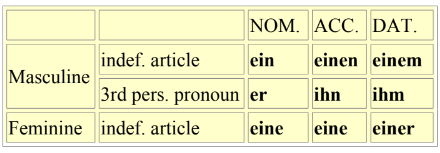

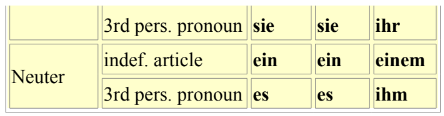

Of course , there are no plural indefinite articles in German or English (ein means “a”. “an”, or “one”) . It is important to see that there is a pattern in the case endings added to ein related to the der-words in the definite articles table above . For example , the dative definite article for masculine nouns is dem — the indefinite article is formed by adding -em onto ein to get einem . The dative definite article for feminine nouns is der—the indefinite is ein plus -er or einer . We will cover these ending changes in greater detail in a future lesson . You will see that there are a number of words (adjectives, for example) whose form relative changes by addition of these endings to signal the case of the noun they modify . Finally , we can see a pattern relationship between these “endings” and the 3rd person pronouns as well :

We could construct a similar table to compare the definite articles to the 3rd person pronouns . And in that case , we would also see how the plural definite articles (die, die, den) compare with the third person plural pronouns (sie, sie, ihnen) .